| Fishing for an extradition

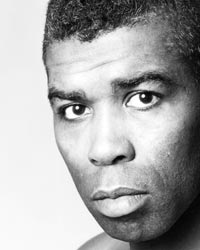

Joseph Pannell, aka Gary Freeman, says he's no Black

Panther.

Three decades later, twisted tale of U.S. fugitive takes another turn By sigcino moyo Family and friends of Joseph Pannell, aka Gary Freeman, slowly make their way around the courthouse at 361 University on another of their now familiar Tuesday-night vigils. On this eve, a mixed group of about 30, many toting signs, have turned up to show their support for Freeman, whose extradition hearing on attempted murder and aggravated battery charges in the alleged shooting of a Chicago cop in 1969 is scheduled to begin here Wednesday (May 25). It's an at times bizarre tale: Freeman jumped bail twice while awaiting trial on charges in the U.S., made his way to Montreal and was ultimately linked to the shooting of officer Terrence Knox via fingerprints taken after Quebec police arrested him 1983 on a customs rap related to his failure to declare a camera purchased in the U.S. Freeman, who is married and has four children, was arrested by Toronto police last July outside the Toronto Reference Library, where he's worked as a research librarian for the last 13 years and where his wife is also employed. He's been in the Central North Correctional Centre in Penetanguishene ever since. The circumstances surrounding Freeman's alleged shooting of Knox are in dispute, and a little curious. In court documents and on radio shows in Canada and the U.S., transcripts of which NOW has reviewed, Knox maintains that Freeman fired on him during a routine stop, hitting him three times in the arm after the officer questioned him about why he wasn't in school. Freeman's lawyers maintain the stop was arbitrary - Freeman was 19 at the time and AWOL from the navy - and that Freeman was acting in self-defence, the details of which will later be released in court. They say he ultimately fled the U.S. because he didn't believe he could receive a fair trial in the then racially riled Chicago. U.S. authorities claim Freeman was a Black Panther, an allegation the family denies. "They came at us with this Black Panther stuff," says Freeman's eldest son, Mace Freeman, a former footballer with the CFL Tiger Cats, whose weary-looking eyes peek our from under a too-small baseball cap. "We didn't want to rush out and say 'No, no, no, he's not,' like we're putting the party down. We respect and admire what the Panthers stood for, but the fact is, my dad wasn't a member." Lawyer John Norris, who with Julian Falconer is part of Freeman's Canadian defence team, thinks the alleged Panther connection is designed to put the defence at a political disadvantage. "One of our concerns is that this is a lightning rod that's been held up by the prosecution and police in Chicago to turn Freeman into something he's not and make this appear to be a very controversial case that ought to outrage the public," says Norris. In documents filed in an Illinois court in April of last year, a special agent with the FBI, Pablo Araya, says that as far back as 1977 Chicago police "developed information indicating that Pannell was residing in Montreal." Why did U.S. authorities wait until 2002 to reissue a warrant for his arrest? Araya explains that "the warrant was mistakenly taken out of Cook County's system for a time." However, from the hundreds of pages of court files and news reports that make up the Freeman file, another theory suggests itself: that Knox, who's no longer with the Chicago police, is using his influence as a former intelligence officer with the department to drive the investigation. Knox has not denied he's been very active in the case and agitating on his own behalf behind the scenes. In court documents he goes so far as to say that he and his family have "feared that he (Freeman) would return to harm us." Norris is understandably tight-lipped about the defence strategy and speaks to NOW in very general terms about the case. "Obviously, we'll present our arguments in court," he says. Whether a black man painted by authorities as a Black Panther who fled prosecution for the shooting of a white cop over 35 years ago can get a fair trial in the U.S. will no doubt form part of the defence's bid to stay extradition. Says Norris, "The broader question is if it's in the interest of justice to send this man to the States, given the passage of time, the nature of the allegations and the racially charged situation at the time." But at this stage, their focus is on whether adequate proof of Freeman's identity has been established. For the most part, the U.S. has had little trouble "getting its man" since the Canada-U.S. Extradition Treaty was ratified in 1976. Changes in 2003 have since made that process easier. The U.S. no longer has to provide certified documents to support an extradition request or receive a green light from the U.S. State Department and Canuck authorities, which in the past reviewed all such requests. Some, like Gary Botting, a BC-based extradition law expert and author of two books on the subject, say the changes render the Extradition Act unconstitutional. "It's sleight of hand. It appears to give all the substantive traditional rights [to the individual], making it look like other extradition provisions found elsewhere in the international community, but it's a straw dog. There's no other country in the world that I'm aware of that's vacated these rights. The new laws are ridiculous." The justice minister can refuse to surrender Freeman if doing so would expose him to a situation that is "simply unacceptable" or would "shock the conscience of Canadians" - two of the acid tests of the constitutionality of extradition." It's rare, but it has happened. Botting points to previous ministerial refusals to surrender. In 1995, Allan Rock refused to ship Richard Witney, a Canadian who jumped bail after getting busted for a 1973 armed robbery in Massachusetts, back to the U.S. Rock's ruling explains that "the length of the delay, the complete rehabilitation of the fugitive, the devastating impact of surrender on the life of a person who has become a valued and contributing member of our society" were taken into account. Freeman's upcoming hearing is similar to a pretrial or preliminary hearing. The role of the judge is very limited, dealing with narrow legal issues. No one is under oath. Nothing is sworn. There will be no testimony from witnesses. The judge will make a ruling based solely on a summary of evidence presented by U.S. authorities. If the synopsis is prepared in conformity with the requirements of the Canada-U.S. Extradition Treaty, the judge must accept it at face value. There's no weighing of evidence or adducing of credibility. The minister of justice then has 90 days to review the decision. The Freeman camp would rather the legal process not drag on and have signalled that they are willing to forgo certain appeal routes. Norris believes that Freeman's legal argument for refusal of surrender will be of interest to the public. "What ought to be clear from many different sources is that this is a man who has lived in Canada for all these years as a model citizen, who is looked up to as a role model by many people," he says. |